Voting is now underway in Charlottesville’s first ranked-choice election to fill two spots on city council. The Central Virginia city is now the second municipality in the Commonwealth to revamp its election process in this way.

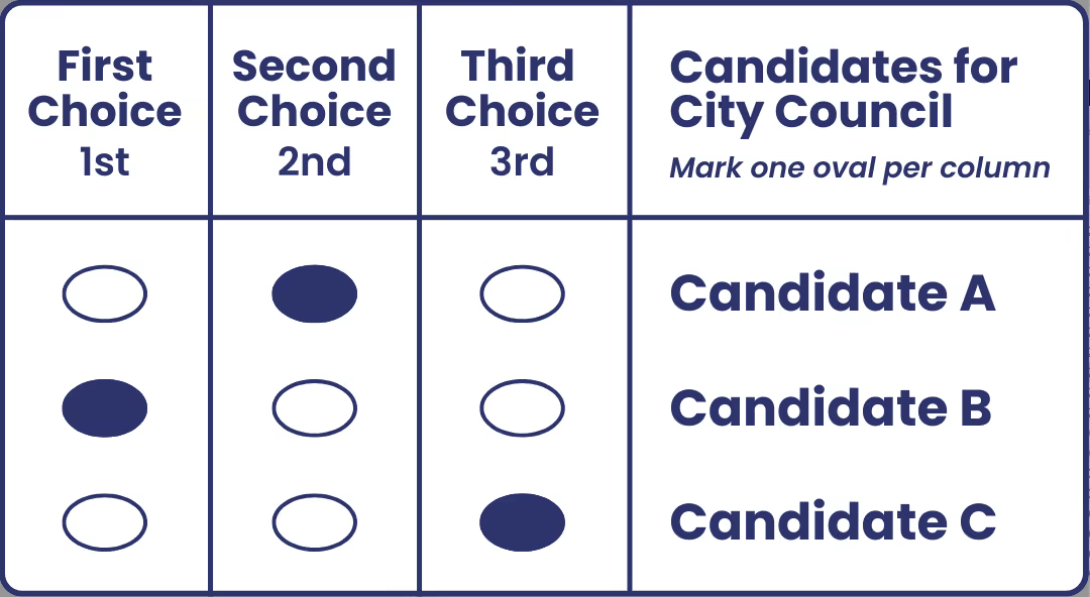

“Under our old system, you could vote for more than one candidate, but you couldn't express a preference between them,” said Karsh Institute Practitioner Fellow Sally Hudson, who, as a Virginia delegate in 2020, led the effort to pass a bipartisan law that allows municipalities in the Commonwealth to use ranked choice voting (RCV).

“That is a problem because you could actually hurt your favorite candidate by voting for a second,” Hudson added. “RCV is a viable solution because you get to rank the candidates in the order that you like them.”

RCV is also trending across the nation: It’s currently featured in public elections in two states and 51 local jurisdictions, according to the American Bar Association.

Why change how votes are cast and counted? RCV allows voters to express their preferences among multiple candidates, which can lead to more representative election outcomes. Research indicates that voters are able to understand the RCV process and use it effectively, ranking candidates based on their preferences.

As Hudson’s nonprofit Ranked Choice Virginia explains: “If no candidate earns enough of the first-choice votes to win, we hold an ‘instant runoff’ to find the winners with broadest support. In each round, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated, and their supporters' votes are transferred to their next choice until we narrow the field to the winners.”

Proponents of RCV praise it for forcing candidates to appeal to a wider range of voters, as they try to earn second- or third-choice votes. In turn, the process discourages extreme positions and promotes coalition building.

Proponents of RCV praise it for forcing candidates to appeal to a wider range of voters, as they try to earn second- or third-choice votes. In turn, the process discourages extreme positions and promotes coalition building.

Detractors say RCV makes the election process more complicated for voters and can delay the results.

"It does take time for people to get used to it,” Hudson said. “But we know in places that have used it, voters adjust pretty fast. In fact, exit polls consistently show that people want to keep RCV once they have it.”

Why Charlottesville?

RCV is especially important for Virginia because, like many Southern states, it adopted block voting in the 1920s, at the height of the Jim Crow era. “Our old voting system sounds simple but was discriminatory by design,” Hudson said. “When everyone gets as many votes as there are open seats, it seems like you're giving everybody the same number of choices, but you're really setting the same people up to win the same way over and over. Block voting is a winner-take-all system that makes it hard for minority groups to get representation on elected bodies—whether they're racial minority groups or political minority groups.”

“Block voting is a winner-take-all system that makes it hard for minority groups to get representation on elected bodies—whether they're racial minority groups or political minority groups.”

Hudson points to nearby cities in Virginia as examples. In barely blue Harrisonburg, when there are three seats open on city council, the Democrats all vote for the Democratic candidates, and the Republicans all vote for the Republican candidates. The Democrats end up winning all the seats because there are slightly more Democrats than Republicans in Harrisonburg.

In Lynchburg, it's just the opposite, with Republicans taking all of the seats.

“In the end,” said Hudson, “the minority party doesn't get any representation on their city councils, even though they make up close to half the population.”

Why This Matters for Democracy

RCV is just one proposed solution to widely recognized issues with the U.S. election system. Other election models include “approval voting” and “cumulative voting”—different approaches with the same goal of creating a more representative democratic process.

“Democracy is iterative,” said Karsh Institute Director of Programming Stefanie Georgakis Abbott. “As we think about how to continue to make our institutions more effective, a big part of that is how we elect our leaders. Sally’s work is getting us to think about how we can use election reform to make democracy function more effectively for everyone.”

“Sally’s work is getting us to think about how we can use election reform to make democracy function more effectively for everyone.”

As an economist, as well as a former Virginia state representative, Hudson comes at this problem from a unique vantage point. “Sally is a perfect fit for the Karsh Institute’s practitioner fellowship program, where we address the really big questions about how to make democracy better,” said Georgakis Abbott. “She has seen what does and doesn't work, both as a lawmaker and as an academic, and she’s applying that expansive knowledge to the implementation of RCV.”

As Hudson points out, RCV has worked elsewhere. Maine and Alaska, the first U.S. states to implement RCV for federal elections, have seen a voting system emerge that doesn’t penalize people for expressing preferences across party lines. “Alaska now has an independent speaker of the house,” said Hudson, “and bipartisan coalitions lead both chambers of its state legislature.” According to an October 2024 Gallup poll, 58 percent of Americans say a third major party is needed in the U.S. because the Republican and Democratic parties “do such a poor job” leading the country.

Last fall, Alaska’s Republican Senator Lisa Murkowski endorsed Mary Peltola, a Democratic candidate for Congress, in an RCV election.

“You can do that in RCV,” Hudson explained. “You can say, ‘I'm a moderate Republican, and I think the moderate Democrat is the best or second-best candidate on the ballot.’ Or vice versa. It sounds like a fairy tale, but it really works. We can have elections where candidates focus more on what they have in common than on what tears them apart.”

“It sounds like a fairy tale, but it really works. We can have elections where candidates focus more on what they have in common than on what tears them apart.”

_____________________________________________________________________

Charlottesville residents can learn more about the City Council election through Ranked Choice Virginia’s Voter Guide. The last day to vote is Tuesday, June 17, 2025.

Ranked Choice Voting Expands Across States and Localities

Karsh Institute Practitioner Fellow Sally Hudson led the effort to bring ranked choice voting to Virginia.

news.virginia.edu

Ranked Choice Voting With Sally Hudson

Advocates of ranked choice voting say it makes our elections better by allowing voters to cast ballots for candidates in order of preference. Others say it’s too confusing. Karsh Institute Practitioner Fellow Sally Hudson explains this new way of voting that’s been slowly spreading across the country.

www.withgoodreasonradio.org