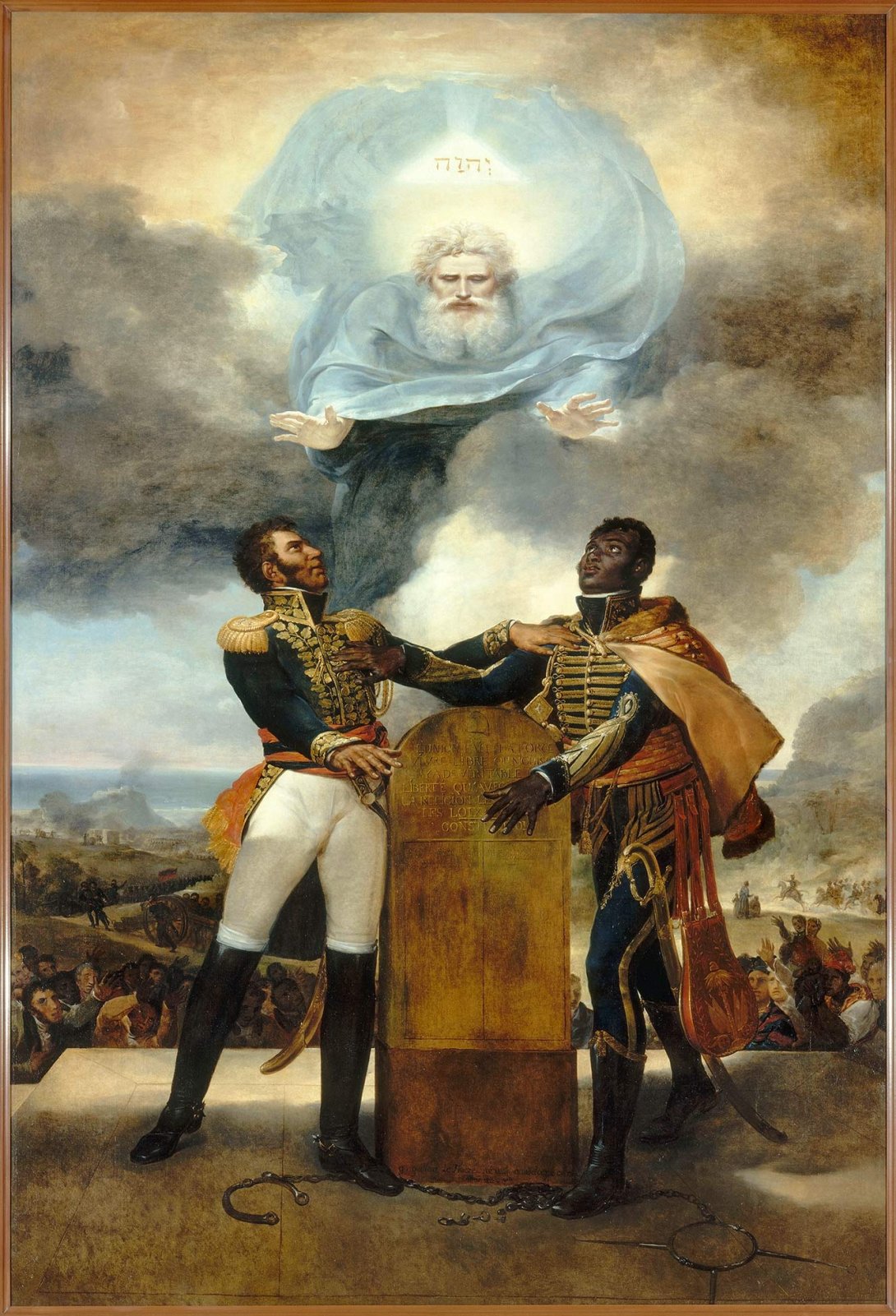

The Karsh Institute's ongoing Touchstones of Democracy event series features a portion of the painting The Oath of the Ancestors, by the Guadeloupe-born French artist Guillaume Lethière. The painting offers an allegory celebrating the founding of Haiti in 1804. It shows two political leaders—Alexandre Pétion and Jean-Jacques Dessalines—uniting to found the new nation with the blessing of god above them. Their hands are on a stone tablet inscribed with passages from the country’s 1805 Constitution and the country’s motto “Unity Is Strength.” The revolutionary slogan “To Live Free or Die” is also written in the stone. The painting has had a remarkable history, crossing the Atlantic Ocean five times since it was created in 1822.

The painting shows two political leaders—Alexandre Pétion and Jean-Jacques Dessalines—uniting to found the new nation with the blessing of god above them.

Lethière was born in Guadeloupe, the son of a white slave-owned father and an enslaved woman of African descent. His father brought him to France where he became a successful and sought-after artist. He received one of the greatest recognitions a French painter could at the time, being named the head of the prestigious French Academy in Rome from 1807 to 1816. He painted members of Napoleon Bonaparte’s family and mentored a range of young artists, including a number of women, during his career. Lethière's contributions have long been overlooked in art history, probably because of his origins, but a recent exhibit developed the Clark Institute in collaboration with the Louvre Museum in Paris has brought him new attention and recognition.

Despite his prominence, Lethière painted The Oath of the Ancestors in secret. At the time, France still had not formally recognized Haiti’s independence and would only do so in 1825 after forcing the country to pay an indemnity to compensate former slave owners from the colony. (You can read about this in the New York Times’ series “The Ransom.”) Lethière’s celebration of the country’s independence was a bold and politically dangerous move.

When he signed the painting, he added that he was “born in Guadeloupe,” something he never did on any other of his works. This was significant as it highlighted his connection to the region. The history of his island had indeed been intertwined with that of Haiti in critical ways. Two years before Haiti gained its independence, slavery had been re-established in Guadeloupe (having been abolished by France in 1794) through a brutal campaign that led to the deaths of 10,000 people. The events in Guadeloupe helped inspire the struggle that ultimately led to Haitian independence, which guaranteed that the residents of that country escaped the re-enslavement Guadeloupeans had suffered at the hands of French troops.

The history of his island had been intertwined with that of Haiti in critical ways.

Once The Oath of the Ancestors was completed, Lethière tasked his son with carrying it secretly to Haiti to offer it as a gift to the government of the country. It was welcomed by them and was ultimately hung in the country’s National Cathedral. It remained there about 170 years, until 1995, when the Haitian artist Edouard Duval-Carrié noted it was in desperate need of cleaning and restoration, and arranged to have it sent to the Louvre Museum in Paris for this work to be completed. It was then returned to Haiti and placed in the country’s National Palace. In 2010, that palace collapse during the devastating earthquake that hit the country. Miraculously, a group of French sapeurs-pompiers who were looking in the rubble for survivors located the painting, and it was once again sent back to France for restoration. It is now on display in Haiti’s National Bank.

Lethière tasked his son with carrying [the painting] secretly to Haiti to offer it as a gift to the government of the country. It was welcomed by them and was ultimately hung in the country’s National Cathedral.

The story and theme of the painting make it a particularly fitting visual for the Touchstones of Democracy series: because of Haiti’s specific history and struggle for freedom, and more broadly, the striving for democracy embodied in the outstretched hands of these two leaders. Behind them, a crowd watches on (including a self-portrait of Lethière at the far left), with landscapes and scenes of battle in the background. At their feet are broken chains.

—Laurent Dubois

Academic Director, Karsh Institute of Democracy